Federal patent authorities rejected Genentech Inc.'s claim of rights over key biotechnology manufacturing techniques, a decision that could cost the South San Francisco company more than $100 million in revenue if upheld.

Genentech is appealing.

Health. Food. Energy.

Maybe by the end of the second day of the scientists and business people were just punchy, but every speaker seemed to have a joke to tell last week at the Florida Venture Capital Conference in Boca Raton.

.. Ernst & Young's Rich Ramko kicked off his talk with a definition tailored for the audience.

Q: What's a biotech company?

A: A pharmaceutical company without revenues.

Actually, the biotech industry is becoming increasingly more stable, Ramko said. "We see an explosion in biotech in the next five years or so."

"It's all happening and it's happening in an incredibly short time."

U.S. scientists are using statistics to identify genetic social interaction traits among animals, thereby finding more productive livestock.

Researchers from Purdue University, the Netherlands and England designed mathematical equations based on traits to choose animals that are more congenial in groups, said William Muir, a Purdue geneticist. The new method is a tool that might contribute both to animal well-being and to securing the world's future food supply, including possibly permitting more animals to be domesticated, Muir said.

He said the tool makes it possible to design selective breeding programs to effectively reduce competitive interactions in livestock. It also aids in predicting how social interactions impact the natural evolution of species.

Plants are being modified to deliver anti-oxidants, which protect against cancer; lipids, which contain essential fatty acids that serve as energy sources; vitamins, such as beta-carotene or vitamin A, which protect against premature blindness and susceptibility to other illnesses; and iron, whose deficiency results in fatigue and decreased immunity, she said.

Bananas and tomatoes are being engineered to deliver, among other things, antibodies for E. coli bacteria-induced diarrhea, a major killer of children around the world. Other plants are being engineered to counteract allergies, Newell-McGloughlin said.

So far, the United States has approved more than 70 genetically modified crops. These crops, which can be grown commercially, include canola, papaya, potato, rice, squash, sugar beets, tomato and tobacco, which is used to help produce a vaccine that fights against a type of lymphoma, said Newell-McGloughlin.

Research is being directed to making already healthy foods, such as protein-rich soy and soy oil with low or no saturated fats, taste better to consumers, Chassy said.

Also being developed are bioengineered trees capable of absorbing harmful chemicals from the soil and plants that can be converted into plastics and industrial products, he said.

At the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, researchers are developing plants that are "phytosynthetically more efficient." These have more leaf surface exposed to the sun, making the leaves more efficient in converting carbon to energy for higher yields, according to Carlos Quiros, a professor and geneticist at the University of California-Davis.

Although considerable research is being conducted by governments, international organizations, foundations, companies and academic institutions, few new products are being commercialized, the scientists said.

They explained that the many, separate country regulatory and patent dispute processes that often are lengthy and costly discourage commercial production. Several of the researchers called for a worldwide regulatory regime.

Also affecting the pace of commercialization is resistance from some consumers to accept that bioengineered foods have been proven to be safe, the scientists said.

As the scandal unraveled in 2005, prosecutors revealed that Mastromarino had netted $4.6 million in three years of back-room dissections. He paid undertakers $1,000 a pop for providing access to the dead, paid cutters $300 to $500 for extracting the most marketable parts, and, according to his lawyer, managed to take home up to $7,000 per body. (One of Mastromarino's former employees contends the boss was pulling in double that.) The New York Police Department later interviewed the families of 1,077 people whose bodies were raided for spines, bones, tendons, and other tissues. BTS had cut deals with funeral homes in New York City, Rochester, Philadelphia, and New Jersey.

Cooke's bones were sold to Regeneration Technologies, one of the country's largest tissue banks. The company says Cooke's bones were deemed unsuitable for implantation, but it can't say the same for other pieces of tissue it bought from Mastromarino. The tissues BTS distributed ended up everywhere from a woman's neck in Kentucky to a man's jaw in Tampa Bay. Hundreds of people wake up every morning knowing that they are partly composed of stolen body parts.

In February 2005, Mastromarino and three others were indicted on 122 charges, including body stealing and opening graves. The grisly story received perhaps more media attention than any such scandal since a wave of body snatching in the 18th century. A February 2006 Paula Zahn Now segment spun the story into the perfect media narrative, complete with a villain, a celebrity, and a whistleblower. But that telling, and many others, failed to point out that much of Mastromarino's basic business model was perfectly legal, common, and necessary to the biotech industry. If Mastromarino had been smarter, he could have made a fortune off body parts while staying well within the limits of the law.

Law and custom both prohibit the sale of cadaveric tissue, a ban heartily supported by bioethicists like Arthur Caplan, the influential director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics. The prohibitionists warn of the degradation and commodification of human beings, but scientific progress has blurred the line between tissue and commodity. Doctors need a constant stream of remains to perform-and profit from-their work. The current compromise treats the body as property once it's in the hands of a corporation but as a "priceless" gift as it passes from a donor's family into the marketplace.

Where does the recovered tissue end up? According to Cindy Speas, WRTC's director of community affairs, the organization is "not involved in any way with anything that is not a not-for-profit." And it's true that the consortium doesn't send tissue directly to corporations. Instead, WRTC provides tissue to LifeNet, another nonprofit, whose mission is to "improve the quality of human life" and "serve the community." LifeNet posted $107 million in revenues in 2004 for "tissue/organ procurement, processing fees, and reimbursements."

From LifeNet, the tissue enters the for-profit system. LifeNet has contracted with LifeCell, the company that makes AlloDerm, along with other "alliance partners" such as Osteotech, the firm that makes bone putty. Standard and Poor's lists LifeCell's value at $888 million. >From there, tissue can end up as replacement skin for a young burn victim or cosmetic filler for a thin-lipped socialite.

Six years ago, two journalists at The Orange County Register undertook the most extensive investigation to date of the legal tissue trade. They linked 59 nonprofit tissue procurement agencies with publicly traded, for-profit firms. They also called each agency for comment, and the recorded answers are a jaw-dropping chronicle of deception and arrogance. The director of the nonprofit California Transplant Donor Network, which at the time was selling bone to Osteotech, admonished the Register, "It is not legal to sell organs and tissue." Others explained that families could not comprehend the distinction between nonprofit and for-profit. A spokesperson for the University of Miami Organ Procurement Agency, which sells skin and bone to the biotech company CryoLife, explained, "We can't be educating donors at the bedside."

They spent months laying the groundwork for a Scottsdale Airpark-based investment bank and advisory firm that they hope will grow with the region's budding biotech industry.

Alare Capital Partners LLC brings together 12 founding partners with backgrounds from pharmaceuticals to mergers and acquisitions to technology licensing. Scientific and business advisory boards add 11 more experts to help generate business leads and provide expertise in technical areas.

"I think it would have been difficult to do two to three to five years ago," Rodgers said of founding the specialty firm in a Valley where other banks didn't last. "There was a sense that there wasn't enough critical mass here, that it was a golf-and-retirement kind of economy. But when TGen (the Translational Genomics Research Institute) and IGC (the International Genomics Consortium) came, that changed everything. It put Arizona on the map."

Now California and the Boston metropolitan area are home to almost all of the few venture capital firms with expertise in funding biotechnology startups. And that, Royston said, poses a problem for the cities in between that are striving to develop their own biotech clusters.

"There's plenty of money out there, but not enough of the kind of venture capital that starts a company," Royston said.

About a year ago, a group from the University of Pittsburgh met with Royston to pitch its idea of spinning off a scientific discovery into a startup biotech company.

"I loved the technology," Royston said. "But in the end, I told them that it was going to require a lot of hands-on work by experienced investors to start the company. I told them to find someone in Pittsburgh to help. I told them that if they were in San Diego, it would be a different story.

Xoma, which Dr. Scannon started in 1981, has never earned an operating profit or marketed a drug of its own. And in the quarter-century since its birth, Xoma has managed to burn through more than $700 million raised from investors and other pharmaceutical companies.

...

Biotechnology has been "one of the biggest money-losing industries in the history of mankind," Arthur D. Levinson, chief executive of Genentech, told analysts in New York last year. He estimated that the biotech industry as a whole has lost nearly $100 billion since Genentech, the industry pioneer and one of its most successful companies, opened its doors in 1976. Only 54 of 342 publicly traded American biotech companies were profitable in 2006, according to Ernst & Young.

AstraZeneca will use Regeneron's VelocImmune technology to discover human monoclonal antibodies. It will do the research work at Cambridge Antibody Technology, a British company AstraZeneca acquired last year. ...

Under the terms of the agreement, AstraZeneca will pay Regeneron $20 million upfront and make up to five annual payments of $20 million. It will also pay Regeneron a royalty in the mid-single digits on any products that come to market.

Thailand backs off threat to break drug patents ( SciDev.net)

[BANGKOK] Thailand has delayed breaking the patent of an AIDS drug and a heart medicine, and entered into negotiations with drug firms to lower the price so that more people can be treated.

The new Pharmacor report Crohn's Disease finds that third-party payers

in both the United States and Europe impose significant limitations on the

use of biologics to treat the disease. One of the limitations in most of

the major pharmaceutical markets is that patients must fail to respond to

at least two conventional therapies, such as corticosteroids and

immunosuppressants, before receiving treatment with a biological agent. As

a result, only a small percentage of Crohn's disease patients will be

treated with biologics during the 2005-2015 forecast period.

Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center scientists have found a set of "master switches" that keep adult blood-forming stem cells in their primitive state. ...

The scientists located the control switches not at the gene level, but farther down the protein production line in more recently discovered forms of ribonucleic acid, or RNA. MicroRNA molecules, once thought to be cellular junk, are now known to switch off activity of the larger RNA strands which allow assembly of the proteins that let cells grow and function."Stem cells are poised to make proteins essential for maturing into blood cells, but microRNAs keep them locked in their place," says cancer researcher Curt Civin, M.D., Ph.D., who led the study. The journal account will appear online the week of February 5 in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

US scientists have cracked the entire genetic code of breast and colon cancers, offering new treatment hopes.

The genetic map shows that nearly 200 mutated genes, most previously unknown, help tumours emerge, grow and spread.

The discovery could also lead to better ways to diagnose cancer in its early, most treatable stages, and personalised treatments, Science magazine reports.

The Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center says the findings suggest cancer is more complex than experts had believed.

The Bush administration was the first to fund embryonic stem-cell research and has devoted well more than $100 million to it since 2001, though only in ways that do not encourage the further destruction of embryos. Bush invokes his faith in explaining his position. ...

There is no ban in place preventing private companies from investing money to fund embryonic stem-cell research. If this research holds as much promise as Mr. Gautreaux feels it does, why aren't private companies lining up around the block to fund it?

There are over four million births each year in the United States, yet Atala calculates that merely 100,000 amniotic stem cell specimens could supply 99 percent of the U.S. population's needs for perfect matches for transplants.

Stem cellsI don't necessarily have an objection to embryonic stem cell research, or Bush's policy. But the issue certainly deserves accurate representation.In a grass roots effort to reject the Bush Administration's recalcitrant position on what promises to be the most exciting area of stopping and reversing - and possible curing - the progression of many major diseases, many states took legislative initiatives to accelerate the finding and development of new stem cell-based research and therapies.

Again, am I missing something in saying that the consequence (perhaps unintended) of Bush's embryonic stem cell funding ban seems to have been to simultaneously start a conversation about bioethics while not managing to stifle innovation?

"There's no way to 100 percent accurately reproduce the host that these compounds grow off of," said Casey Alexander, analyst for Gilford Securities. "Therefore it can never be functionally identical."

The only way for a biogeneric company to produce an exact copy of a brand-name biotech drugs, said Alexander, is to "sneak into the factory and to steal the host, which is illegal."

Barr also has an eye on the future in biogenerics, or generic versions of biotech drugs.

Biotechnology, a method of drug development that uses living organisms, was established in the 1970s with the debut of Genentech, the world's second-largest biotech in terms of sales behind Amgen. Biotech drugs have been in existence long enough for the patents to run out on some of the industry's older products.

But the FDA does not have the regulatory process necessary for the creation of biogenerics, meaning that biotechs in the U.S. do not have to compete against low-cost generics.

Missing the biogeneric boom

However, Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., is trying to change that. Waxman became one of the most important figures in the drug industry in 1984, when he and Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, drafted the Hatch-Waxman bill that created the regulatory process for generic drugs in the U.S.

A staffer for Waxman said he plans to submit a bill in the next few weeks to lay the foundations for the biogenerics industry in the U.S. This is on top of another biogenerics regulatory bill that Waxman filed last year with Sens. Charles Schumer and Hillary Clinton, both Democrats from New York.

While biogenerics hasn't gotten off the ground in the U.S., it's up and running in China and Eastern Europe, where companies produce generic versions of biotech drugs. In 2006, Barr bought the Croatian company Pliva, the biggest drugmaker in Eastern Europe and a pioneer in the emerging but risky field.

Sawyer of Leerink Swann said in a published note that Teva and Barr are the "best positioned to benefit from the biogeneric opportunity" because of their involvement in the multinational markets, though the potential benefits from the U.S. market are four or five years away.

"My view is that by 2010 you'll see biogenerics in the U.S.," said Forman. "The U.S. will be the last country in the world to have biogenerics."

This would avoid the costs and risks of biogeneric development and regulatory approval while delivering the benefits of lower costs to payers. The original maker of the product should be happy too. Although their price will be lower than it is today, they won't have to share the market with generic players or spend money blocking the entry of new players. They will still enjoy a substantial period of high margin sales as they do today. It just won't go on forever.

- Allow biotech drugs to be approved and marketed as they are now, without price regulation

- After patent expiration or after a certain number of years on the market, regulate price. The price could be based on cost of goods, a percent of the previous selling price, or some other mechanism

When, at some point in the future, science improves to the point where truly identical biogenerics can be developed, these rules could be revisited.

Colorado State University announced a new program, called MicroRx, which is intended to move infectious-disease research to market faster than existing technology-transfer models in the state.

CSU held a briefing about the concept Thursday at its office in downtown Denver.

MicroRx is the first of CSU's "superclusters" -- alliances of academic researchers, economists and business experts. The Fort Collins-based university began developing the superclusters concept in 2004.

As a nonprofit entity, MicroRx will focus on infectious disease, and biomedical research and development -- a niche that has gained CSU renown in recent years.

In the meantime Congress has stepped in. On Jan. 17, Senator Herb Kohl (D-Wisconsin) proposed a bill that would make it "unlawful" for a settlement between a drug patent holder and a generic challenger to "include an exchange of anything of value." Expect major pushback from both generic companies and the notoriously powerful Big Pharma lobby.

Besides Congressmen, the FTC has another ally - Bernard Sherman, the Apotex CEO. Here's how he played out his "settlement" with Bristol and Sanofi: First, Sherman asked the patent holders for permission to launch generic Plavix right away should the FTC and state attorneys general turn the settlement down. (The regulators had that power because Bristol was operating under a consent decree stemming from past bad behavior over its patented drugs.) Bristol and Sanofi agreed and said generic Plavix could stay on the market for a window of five days in such an event.

Then Sherman's lawyers told the regulators that Bristol had offered Apotex unwritten side arrangements. The regulators rejected the settlement. They decline to say why, and Sherman says he thinks they would have rejected the deal regardless of the side arrangements.

Apotex immediately flooded the market with generic Plavix it had already made, selling a six-month supply before Bristol could get an injunction to stop it. Instead of the $40 million that it would have collected in the settlement, Sherman's company probably made multiples of that by actually selling the drug. In September, Dolan - long under fire - lost his job, at least partly as a result of this bungled deal.

The Justice Department has launched a criminal antitrust investigation into the settlement. Bristol denies that it ever made any unwritten side agreements. (It also says that the $40 million in the settlement would not have been a payment to keep generic Plavix off the market, but rather one to reimburse Apotex for what it had manufactured.)

Sherman won't actually come out and say that his settlement agreement was a ruse, but he has said that he extracted concessions from Bristol fully expecting that the regulators would scuttle it. He says Apotex has never settled a patent case: "Both generics and brands are trying to make more money at the public expense," he says.

Generic drugmakers produce and sell drugs after patents expire. Generic drugs are most profitable in the six months following patent expiration, when the price only drops by about 40 percent because there is only one generic drugmaker producing it.

Generic companies fight over this six-month window of exclusivity, because the price drops another 40 percent when it runs out, cutting into profits.

Here are some recent skirmishes that have seen developing countries protest against pharmaceutical companies' drug patents:

In 2003, varieties of hybrid cotton seed known by the brand names Ganesh and Brahma were the popular choice among farmers in Gudepad, a village in the Warangal district of the state of Andhra Pradesh in India. By 2005, a majority of farmers throughout the entire district had switched to RCH-2 Bt, a genetically modified strain of cotton designed to produce its own insecticide.

The biotech industry would like us to believe that the migration to GM cotton was a result of individual farmers' testing out various seeds and coming to the sage conclusion that RCH-2 Bt performed the best. In contrast, anti-GM activists, even as they claim, despite the evidence in Warangal, that farmers are rejecting GM crops, also stress that whatever adoption does occur is likely the result of corporate propaganda and distribution muscle. Oh, and the new strains don't work as advertised, either.

But as is so often the case, neither side's explanation fully captures the situation on the ground.

There has been a lot of attention in recent years on the outsourcing of pharmaceutical research and manufacturing to India. While domestic pharma majors may be the beneficiaries of this trend, the original giants of outsourcing are not lagging far behind. IT behemoths like TCS and Wipro are grabbing a piece of the pharma outsourcing pie by getting involved in clinical data management. TCS recently secured a deal with Eli Lilly, which includes the establishment of a facility in Noida. Other pharma companies too have outsourced clinical data management operations to India including Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk and Wyeth.

There are over 2,000 Chinese-foreign joint ventures in the biomedical sector, including major players like Roche (RHHBY), Novartis (NVS), GSK (GSK), Pfizer (PFE), Medtronic (MDT), Becton Dickinson (BDX) and Inverness Medical (IMA), just to name a few. Most are significantly expanding their operations and are investing heavily in research and development to move beyond just manufacturing and distribution. China is encouraging and even subsidizing this migration, as it recognizes that to sustain its incredible historic growth rate of 9% per year, it must move its economy toward R&D.

WASHINGTON--(BUSINESS WIRE)--The Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) today praised the far-reaching initiatives contained in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's 2007 Farm Bill Proposals to encourage the production of biofuels and biobased products from renewable agricultural resources, as well as ensure fairness of international trade for agriculture.

"The 2007 Farm Bill proposals show the Administration's support of biotechnology in both industrial and agricultural applications," said Jim Greenwood, president and CEO of BIO. "We greatly appreciate the Administration's demonstrated commitment to support companies researching and commercializing both ethanol from cellulose and biobased products from renewable agricultural resources. The proposals related to international trade illustrate the importance of internationally accepted regulatory standards, many of which affect biotech crops."

The Bush administration was the first to fund embryonic stem-cell research and has devoted well more than $100 million to it since 2001, though only in ways that do not encourage the further destruction of embryos. Bush invokes his faith in explaining his position. ...

There is no ban in place preventing private companies from investing money to fund embryonic stem-cell research. If this research holds as much promise as Mr. Gautreaux feels it does, why aren't private companies lining up around the block to fund it?

On February 5, 2006, the U.K. Patent Office published the final report on the its "Public consultation on level of the inventive step required for obtaining patents:

Anonymous said...

Lincoln - The opportunity to grow medicine in cornfields may have slipped away from Nebraska and Iowa farmers for at least the time being.That'll do 'er!

The biopharming movement - the attempt to put genes into plants that will reproduce into therapeutic drugs - continues to advance, but companies are shying away from corn as a potential drug-making factory.

"I see it as a lost opportunity," said Aurora, Neb., farmer Richard Schaffert, who was among the Midlands farmers in 2002 who planted test plots of corn for a biopharming company called ProdiGene Inc. of College Station, Texas.

The crops-to-drugs industry suffered a major setback when gene-altered corn plants from the previous year's ProdiGene tests emerged among soybeans growing in the same fields.

In Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) countries, in spite of the abundance of natural resources and continued investments in development, poverty and food insecurity affect more than 55 percent of the rural population. Fifteen years ago, plant biotechnology comprised only a few applications of tissue culture, recombinant DNA technology and monoclonal antibodies. Today, genetic transformation, and marker-aided selection and breeding are just a few of the examples of the applications in crop improvement with profound implications for the LAC Region.

Plant biotechnology applications must respond to increasing demands in terms of food security, socio-economic development and promote the conservation, diversification and sustainable use of plant genetic resources as basic inputs for the future agriculture of the Region.

The deal with Elbion focuses on discovering drugs to treat schizophrenia, while collaborations with Nautilus Biotech and MediVas are aimed at developing more advanced haemophilia treatments, either by developing new drugs or a better drug delivery system.

African Heads of State have endorsed a 20-year biotechnology action plan for the African Union, but held off committing to a science and innovation fund.

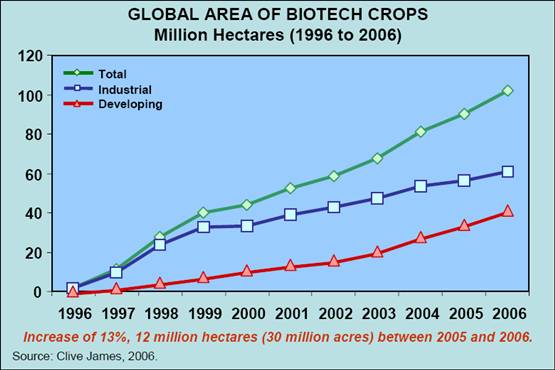

SAN FRANCISCO, FEB 2: A biotechnology advocacy group reported on Thursday that a record number of crops were planted worldwide last year, but critics complained the gains did not go beyond making corn, soy and cotton crops resistant to weed killers and bugs.

None of the genetically engineered crops for sale last year were nutritionally enhanced and much of the output feeds livestock, which critics said undercuts industry claims that biotechnology can help alleviate human hunger. Still, the report prepared by the industry-backed International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications touted the record as evidence that crops engineered to cut pesticide use can ease poverty and financially benefit small farmers around the world.

According to investment bank EG Capital, the 121 biotech companies on the ASX have a total market capitalisation of $6.9 billion. That's equal to the market cap of just one US biotech company, Chiron (the fifth-biggest US biotech stock).

MAYBE we should have known that a company selling a cure-all for pigs and chickens might be risky. But I do feel sorry for anyone who bought the failed biotech wonder stock Chemeq in recent years — especially those who paid $8 a share back in 2004.

Because the way things are going, the last share trade at 21 cents is beginning to look a little on the high side.

The managers of Chemeq are holed up in Perth this weekend wondering how they can come up with $60 million they have been ordered to pay bond holders by the WA Supreme Court. It won't be easy — the total value of the company is $21 million.

Chemeq is not the first biotech company to lose heaps of money for shareholders and make a joke of the sector, and it won't be the last. But it's worth looking at why this company, which planned to develop and manufacture an alternative to antibiotics in farm animals, has bitten the dust. ...

For anyone interested in investing in, or thinking of pursuing a career in biotech, whether at a large company or a small startup, here are five positive indicators of how viable the industry is today. These signs speak volumes of the potential and popularity of biotech today among investors and politicians alike.

I mock Lexicon Genetics, er, Pharmaceuticals, but in all seriousness, why did this rejuvenation take so long? Human Genome Sciences (HGSI - Cramer's Take - Stockpickr - Rating) and Millennium Pharmaceuticals (MLNM - Cramer's Take - Stockpickr - Rating) learned the painful lesson years ago that spending your days poking around human DNA might be noble work, but it certainly wasn't a viable business model. The real money is in developing, and hopefully selling, drugs.

02 Feb 2007 - Interferon-beta is used for multiple sclerosis therapy. An interferon-beta protein developed at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB, Stuttgart, Germany, in collaboration with CinnaGen company, Tehran, Iran, is now the first therapeutic protein from a Fraunhofer laboratory to be approved as biogeneric / biosimilar medicine.

Although human embryonic stem cells have greater potential than adult stem cells, embryonic stem cell research hasn't kept up pace with adult stem cell research. The biggest advantage of adult stem cell is it is free of ethnic controversy. The first adult stem cell based treatment will be on the market within next couple years, much sooner than embryonic stem cell. For the last few days, I tried to collect information for adult stem cell biotechnology and industry. I was very impressed by the progress they have made.

In the latest of several recent lucrative deals between Bay Area life-science companies and major drug makers, Anacor Pharmaceuticals of Palo Alto said Friday that Schering-Plough has agreed to pay it up to $625 million for its toe-fungus treatment.

...

Last month, Amgen of Thousand Oaks in Southern California agreed to a deal worth up to $725 million to help develop heart-failure treatments with Cytokinetics of South San Francisco. Since 2004, Amgen also has purchased three Bay Area companies -- Avidia of Mountain View, Abgenix of Fremont and Tularik of South San Francisco -- for a total of $3.88 billion.

In October, Merck of Whitehouse Station, N.J., announced it was paying $1.1 billion in cash for Sirna Therapeutics of San Francisco, which had been developing drugs to combat cancer, the virus that causes AIDS and other diseases.

And in August, GlaxoSmithKline of London announced it would pay up to $1.5 billion for the rights to treatments being developed by Mountain-View based ChemoCentryx for bowel and inflammatory disorders.

Under the terms of the agreement, Roche Pharma will gain access to all the features of the CNS subset of the DrugTarget Database(TM). These include informatics on more than 3,400 genes, 886 comprehensive immunohistochemistry (IHC) reports with localization information on more than 450 potential drug targets selected by pharmaceutical company subscribers, and innovative search and analysis tools. LifeSpan continues to build the database by publishing localization data on an undisclosed number of additional protein targets each year.

The new Congress is coming out of the gate bristling with proposals for reforming the FDA and putting new reins on the biopharma industry. New measures would restrict drug advertising as well as create a new office of drug safety to oversee medications after they're approved. Similar measures have been floated before and never had a chance. But the new Democratic majority--allied with several senior Republicans angered by the agency's safety record--appear emboldened to act fast, which has industry officials somewhat alarmed.

The key concern among the trade groups is that the reformers are likely to piggy-back on the reauthorization of the user-fee bill, an essential piece of legislation for financing the FDA. Billy Tauzin (photo) at PhRMA says the bill could become a "Christmas tree" loaded with new measures. The drug industry is banking on a compromise pact with the FDA that increases user fees by about a third, up to $393 million next year. And they're hoping the extra money will help grease the tracks to get the bill through without reformers tacking on any new safety measures. Without a new user fee authorization the agency's drug regulation work will essentially be frozen by late summer, setting the stage for a major showdown in Washington.

A look at how Congress may deal with the issue of biogenerics, with John Calfee, American Enterprise Institute Resident Scholar; Kathleen Jaeger, Generic Pharmaceutical Association CEO and CNBC's Sue Herera

"I think that given the pressure the FDA is under for drug safety, the FDA is going to move very slowly to allow anything purporting to be a generic version of those drugs even if the law is changed opening the way for that kind of thing. And I think that doctors are going to be very slow to switch to those drugs..."

In an earlier article, I reviewed Pisano's book Science Business: the Promise, the Reality, and the Future of Biotech, in which the Harvard business professor provides compelling evidence showcasing the ineptitude of the biotech industry over the last three decades.

But a recent report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) paints a different picture all together. In the report, for which data was collected from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the GAO found that the pharmaceutical industry was in fact losing to the biotech industry in the number of new molecular entities (NMEs) approved by the FDA over the last few years.

2003 was the first time that biotechs had a higher number of NMEs approved, and the gap has widened since then. Pharma companies had 16 approvals that year, compared to biotechs' 18.

...

One major finding of the GAO report however had nothing to do with competition from the biotech industry. From 1993 to 2004, the report found that while R&D spending by the pharmaceutical industry increased by 147%, drug approvals only increased by 38%.

While producing generic equivalents of these drugs might (it's still somewhat of a gray area) technically not be illegal -- Thailand is a member of the World Trade Organization, and developing countries have until 2016 to implement protections for pharmaceutical patents -- the country is still obligated to pay and negotiate licensing fees for the drugs, or else risk having a trade complaint filed against it.

Interestingly enough, discouraging pharmaceutical innovation with compulsory rules forcing the price of drugs down doesn't really help countries save on drug costs. The FDA has a white paper that shows that prices of generic drugs are cheaper in the U.S. than their Canadian-branded and generic counterparts, even though the U.S. gives stronger "incentives for R&D" spending.

Tailoring options to account for firm differences, says Arvids Ziedonis, assistant professor of strategy at the Ross School, can facilitate the licensing of university inventions to industry yet protect against suitors who seek to absorb knowledge about new technology during the option period without subsequently purchasing licenses.

...

The relationship between technological knowledge and the likelihood of licensing tends to be quite different for companies that purchase options prior to making licensing decisions, however. In such cases, firms that hold patent portfolios concentrated in areas related to the university inventions ( i.e., high-focus firms) are less likely to subsequently license the university patent at the end of the option period. Ziedonis suggests several explanations for this.